Over the past two decades, we have succeeded in increasing access to facility-based childbirth with skilled birth attendants around the world. Yet, we have not seen the expected reductions in maternal and newborn mortality with improved access alone. A failure to focus on improving the quality of care, along with affordable access to care, is widely acknowledged as the reason. Currently, many interventions target one or two of the major causes of death, but these strategies have not integrated a broader package of scalable improvements in quality of care.

The biggest opportunity to save lives in childbirth now lies in improving the quality of care, both the provision and experience of care for women, newborns, and frontline health care providers.

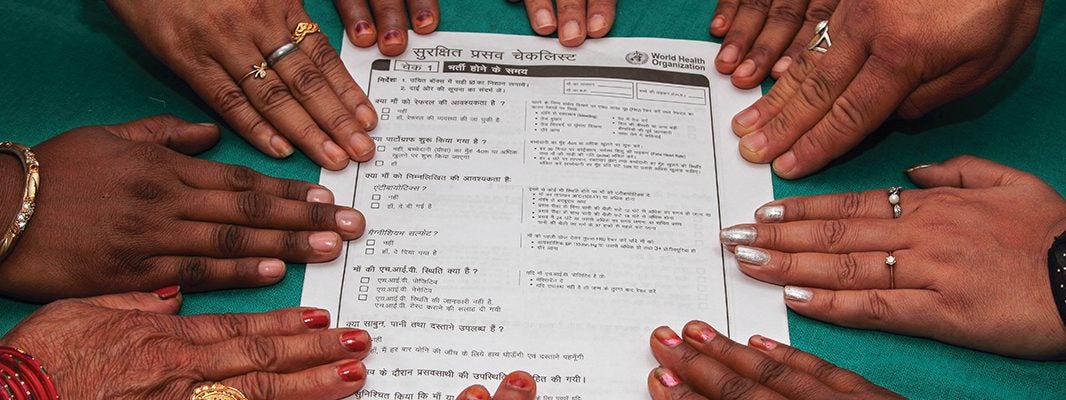

This report synthesizes lessons learned and offers global recommendations from the BetterBirth Study for policy makers, program designers, implementers, and health system leaders. BetterBirth, one of the largest studies ever conducted in maternal and newborn health, used a scalable intervention targeting the seven leading causes of maternal and newborn mortality during facility-based childbirth. The study, which took place from 2014 to 2017 in 120 frontline facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India, focused on an eight-month peer-coaching-based program to implement the World Health Organization (WHO) Safe Childbirth Checklist. We found that the BetterBirth implementation of the Checklist, coupled with coaching and data feedback, improved adherence to essential birth practices. Yet, these improvements did not reduce overall maternal and perinatal mortality in primary-level facilities1.

During 2018, we analyzed more than 200 million data points from more than 157,000 women study participants and their newborns. Our goal was to discover ways to improve facility-based childbirth care to lower morbidity and mortality. We found there is no magic bullet—no individual clinical practice correlated with better outcomes. Rather, lower mortality correlated with an increased number of completed essential birth practices, regardless of which practices were done.

However, we found even this was insufficient to drive the change required to save lives at scale. Improving individual birth attendant performance was not enough. To deliver the comprehensive bundle of essential birth practices and achieve sustained outcomes, birth attendants should be supported by a health system that is integrated, cohesive, and seamless.

The BetterBirth data provide an evidence base for key strategies needed at all levels of the facility-based childbirth ecosystem: birth attendants, facilities, health systems, and women and their communities. The following recommendations from the BetterBirth experience offer a path to high-quality, person-centered childbirth care around the world.

The Intervention:

Quality Matters

The BetterBirth intervention (WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist + coaching + data feedback) demonstrated it is possible to improve multiple components of quality of care, including uptake of essential birth practices among birth attendants. Achieving this improvement in quality is critical to reducing maternal and perinatal disease, complications, and death.

To achieve wider-scale impact on outcomes, program leaders, funders, and global health agencies should consider

- adapting the WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist to the local setting and integrating the Checklist into the workflow;

- tailoring the implementation strategy to the facility’s readiness level; and

- nurturing leadership commitment to quality improvement.

Birth Attendants:

Competency & Workplace Matter

Birth attendants around the globe encompass a diverse group of providers, from traditional birth attendants to nurse midwives to physicians. Ideally, these caregivers have the skills and authority to provide quality care while making childbirth a positive experience.

However, the BetterBirth Study found birth attendants often lacked individual competency and faced competing priorities and pressures in the workplace—including intertwined clinical, administrative, and financial pressures.

To remedy these challenges, birth attendants should have appropriate skills, continuous training, and advanced professional development to sustain their competency. They should also be supported by the workplace environment to accomplish their day-to-day responsibility for providing high-quality care. Such an enabling environment includes physical and psychological safety and security, a manageable clinical and administrative workload, and appreciation for a job well done. Incentives from inside and outside the facility need to align with best clinical practices. Simply, support structures within facilities should remove barriers to doing the right thing.

The Health Facility:

Readiness Matters

We found substantial variation in mortality across facilities and searched for reasons why such vast differences existed. Historically, facility needs assessments focus on easily measured inputs, such as the number of staff or number of delivery rooms.

Instead, we found it is often the overlooked, difficult-to-quantify factors about a facility’s readiness to take on quality improvement initiatives—leadership commitment, facility capability and capacity, organizational culture, and social context—that powerfully promote or hinder quality care.

With the critical information on all domains of facility readiness for quality improvement, interventions and implementation pathways can be tailored and strengthened to support early adopters and to work with resisters until they are ready to implement quality improvement programs. Program implementers should consider using qualitative methods, such as staff interviews and observation, to more fully understand facility-level culture, teamwork, and problem-solving as they design, adapt, and implement quality improvement interventions.

The Health System:

“Systemness” Matters

Often, the building blocks of a health system are in place; however, they are rarely integrated or cohesive across the continuum of care. No one facility, birth attendant, or other component of the health-care system is responsible for all the gaps in care.

The BetterBirth Study uncovered worrisome fault lines in the critical connections within the health system, particularly in the referral system that manages the most vulnerable women and newborns in childbirth. With the concept of “systemness,” we focus less on the building blocks, such as supply systems, health care workforce, financing, or the individual health facilities, and more on the connections among them, such as communication and teamwork.

Systemness is the glue that holds all the pieces together; it is the vertical, horizontal, and diagonal integration across the system that matters. Key recommendations for solving these problems include

- developing continuity of care from the antenatal to intrapartum to postpartum periods;

- bolstering communication between frontline and higher-level health care facilities; and

- strengthening transportation between facilities and supply line integration.

Women & Community:

Power Matters

Women and newborns must be at the heart of person-centered care if we want to improve their health outcomes. To achieve this, strategies must account for their social and economic context and prioritize what matters to them.

In the BetterBirth Study, we found the power dynamics among women, their communities, birth attendants, and the health system can promote or impede quality care. For example, women consistently received substandard and sometimes disrespectful care. Yet, most women reported high satisfaction with their care, which underscores low expectations and normalization of poor care. These contradictory findings suggest all individuals within the childbirth ecosystem should be sensitized to appropriate expectations for high-quality, dignified person-centered care.

To put women at the center of childbirth care, we call for validated metrics of respectful care and patient satisfaction, birth attendant training and support in delivering person-centered care, and advances in women’s empowerment. ■