In the nearly two decades since the United Nations adopted its ambitious Millennium Development Goal 5—to improve maternal health—the death rate among childbearing women has fallen dramatically.

A larger proportion of women are giving birth in health facilities and with the assistance of skilled birth attendants, rather than at home with an untrained family member or community member. In India, the Janani Suraksha Yojana program—a safe motherhood intervention run by the country’s National Rural Health Mission—successfully increased the rates of facility-based childbirth since 2005 by offering financial incentives to women through conditional cash transfers.

However, this progress was not seen in other services across the continuum of care. For example, most recent national surveys showed that only 51% of women had at least four antenatal care visits.14

Despite the dramatic scale-up of facility-based deliveries globally, reductions in maternal deaths have not been as large as public health experts had hoped. In recent years, progress has plateaued.

One reason for this disappointing trend concerns quality of care, which is addressed through innovations like the Safe Childbirth Checklist. Another is that too little attention has been paid to the women themselves and to their expectations and experience of their health care encounters. The 2016 World Health Organization quality of care framework for women and newborns underscores this disconnect; the experience of care for pregnant women during childbirth is just as important as the provision of care in achieving person-centered results.7

In the ecosystem of facility-based childbirth care, women and their communities are deliberately placed at the center so they are seen, heard, and prioritized. That should be done with consideration for the broader context of women’s communities.

Women face a multitude of power dynamics and cultural practices—both in their communities and in the health system—that can hasten or delay when they seek care, amplify or stifle their voiced preferences, raise or lower their expectations for quality care, and normalize or sanction disrespectful treatment. These ubiquitous but often hidden power dynamics must be taken into account in the design of any intervention that aims to raise demand for quality care.

The Childbirth Experience

The well-documented link between women’s social and economic advancement and their health outcomes during childbirth does not tell the whole story. Just as important as these sociodemographic drivers are women’s expectations about health care and childbirth. In the BetterBirth Study, coaches often noted poor conditions at health facilities, which sometimes lacked adequate food and bathrooms for patients, and did not have the space or resources to allow for privacy or accommodate family members (from coaching observations and notes). Because of space constraints, single beds had to hold two women and two newborns at times. These conditions were often viewed as inconvenient, but normal.

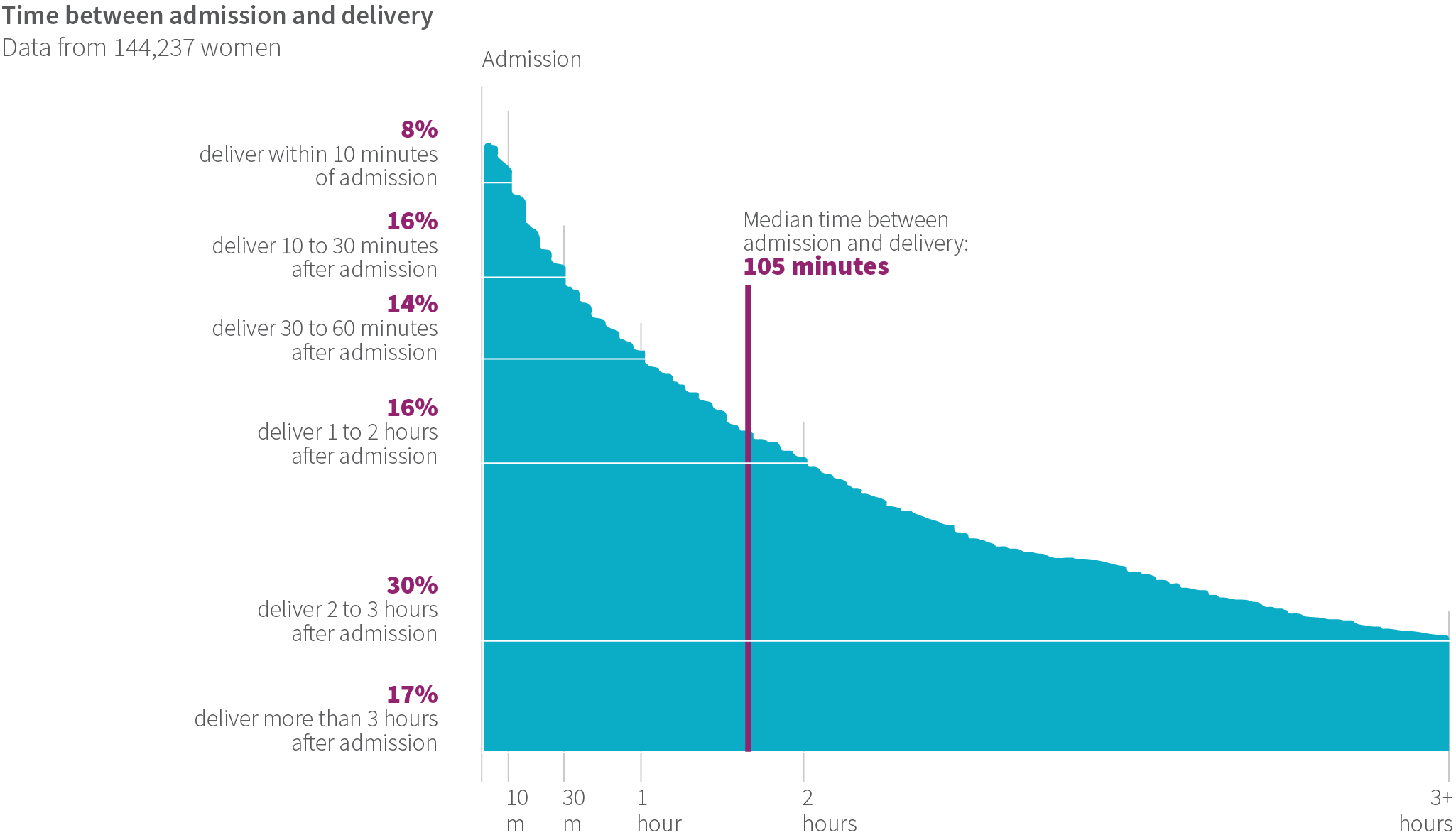

It’s no wonder, given the uncomfortable conditions, that women spent minimal time at health-care facilities. In the study, the median amount of time a woman spent at a facility from admission to delivery was only 105 minutes. Based on interviews, we estimate the women left or were discharged approximately two to six hours after giving birth. While women ostensibly received skilled attendance at birth, many actually spent very little time at the health facility.

This brief time in the facility created challenges for care around childbirth. When a woman arrived late in labor, it hindered birth attendants’ ability to identify complications before delivery, and left precious few minutes to refer the woman to a higher-level facility before delivery, if needed. Likewise, time constraints after delivery limited birth attendants’ ability to identify maternal or newborn complications, such as hemorrhage or respiratory distress, respectively, which can occur after a woman and newborn return home. Indeed, the WHO recommends both the woman and newborn stay at a facility for the first 24 hours after birth to monitor their recovery and address complications immediately.

Moreover, when women leave a facility too soon—either by choice or because of space constraints—they have less access to counseling and support on important topics such as breastfeeding, infant care, immunizations, and danger signs. In the BetterBirth Study, birth attendants spent very little time on counseling (see Chapter 2: Birth Attendants); on average, the discussion about danger signs lasted a mere 28 seconds (41 observations). One week after delivery, only 6% of the more than 157,000 women surveyed could name any danger sign that would prompt them to seek medical care.

ONLY 6% OF WOMEN COULD REMEMBER ANY MATERNAL OR NEWBORN DANGER SIGN

Maternal Danger Signs

– Bleeding

– Severe abdominal pain

– Fits or seizures

– Severe headache or visual disturbance

– Breathing difficulty

– Fever or chills

– Difficulty emptying bladder

– Dribbling of urine

– Severe vaginal pain

– Pus or foul-smelling discharge from vaginal area

– Swollen, red, or tender breasts

Neonatal Danger Signs

– Fast / difficulty breathing

– Fever

– Unusually cold

– Stops feeding well

– Less activity than normal

– Whole body becomes yellow

– Looks sick (lethargic or irritable)

– Looks yellow, pale, or bluish

– Body is arched forward

– Irregular movements of the body, limbs, or face

The overuse of medications such as oxytocin to speed up deliveries may be another factor contributing to women’s abbreviated facility stays. The study’s qualitative interviews revealed many women had received oxytocin in the community or at home before reaching the facility. Birth attendants reported feeling pressured by families to administer additional oxytocin, perhaps to conform to social norms because conditions at the facility were unpleasant for women and their families (i.e., there was no place for families to sit, no pain control, and no food to eat). These same stresses prompted community health workers to persuade birth attendants to give oxytocin. Indeed, prior to the intervention, independent observers documented that 80% of women whose birth was observed (603 births observed) received oxytocin to augment labor upon arrival at the facility. While it is difficult to ascertain the true incidence of labor delays that would warrant labor augmentation in this environment, these rates are exceptionally high, given the lack of maternal and fetal monitoring and lack of cesarean delivery capability at these facilities in the event one is indicated.

Globally, numerous studies have shown advances in women’s education, income, and empowerment are associated with lower maternal and perinatal mortality. Findings from the BetterBirth Study confirm this trend. The most powerful predictor of perinatal death in any facility was the level of women’s literacy in the district where the facility was located. Globally, we should continue to strengthen education and empower women’s voices in the effort to improve health outcomes.

The Quest for Dignified Maternity Care

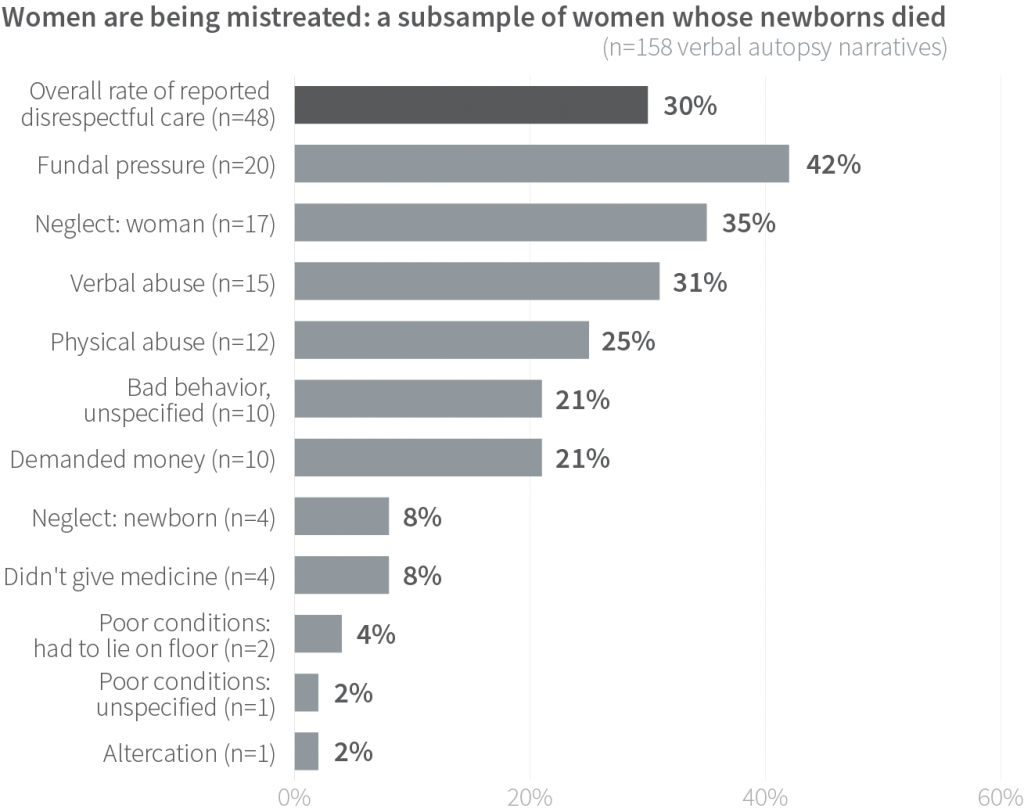

The imperative for respectful maternity care has gained global attention, and was underscored in the WHO quality of care framework. Yet, in a subsample of women whose newborns died (n=158 verbal autopsy narratives), 30% reported some form of disrespect or abuse. Among the examples of mistreatment were overall disrespectful care, neglect, verbal abuse, physical abuse, demands for money, neglect of the newborn, and such poor facility conditions that women in labor were forced to lie on the floor.

In this subsample of women whose newborns died, neglect was common (35%) among those who reported disrespect or mistreatment. Women reported being examined upon arrival, then left alone for hours until delivery. They told of receiving no care or attention during nighttime hours.

Verbal abuse (31%) and physical abuse (25%) were also prevalent. And such incidents of abuse were not isolated—many forms of mistreatment could occur during a single stay at the facility. Indeed, 17% reported three types of abuse; 38% reported two types of abuse; and 38% reported one type of abuse. Overall, 63% reported experiencing two or more types of disrespectful care. Such discourteous and even contemptuous treatment naturally drives women and family members to minimize the time spent at a health care facility.

Paradoxically, these negative experiences are not reflected in women’s reported overall perception of the care they received. For example, 95% of the almost 150,000 women surveyed reported high satisfaction with their care during childbirth, and most said they would recommend the facility to a friend or family member (of note, women and families who experienced a death were not asked satisfaction questions).

BetterBirth call center staff responsible for the majority of all patient follow-up reported that women would spontaneously recount instances of neglect, poor care, and abuse during childbirth, yet insist they were satisfied with care when asked directly. The disconnect between some experiences of disrespectful care and the overall positive accounting of care may point to women’s low expectations and their disempowerment within the system, as well as a lack of psychological safety in reporting poor care.

A CLOSER LOOK AT DISRESPECTFUL CARE

One woman in the BetterBirth Study recounted her experience of disrespectful care and physical abuse during labor and delivery. The woman described receiving multiple injections to increase pain (contractions) before the baby started to deliver. At some point, the baby became stuck; the woman said the nurse told her to exert force, and scolded and slapped her. According to the woman, a facility cleaner began pressing on her abdomen to hasten delivery. Eventually the baby boy was born.

Financial Transactions

Around the globe, financial barriers often impede access to proper childbirth care, and this proved true as well in the BetterBirth Study. While Uttar Pradesh mandates free childbirth care in public facilities, women and their families are often involved in financial transactions during labor and delivery.

While we did not interview all women about financial transactions, the women interviewed during verbal autopsy for their newborns (158 interviews) did mention payments and other transactions. Among this subset of women, 82% said they paid for childbirth care. Sometimes, these payments were voluntary; more often, they were forced or coerced. Frequently, women or their families had to pay additional fees for medications, in-facility stays, and other aspects of care. Women reported paying slightly more for care in intervention facilities than in control sites, which could be due, in part, to the additional care given to the women, such as blood pressure measurement, fetal monitoring, and follow-up.

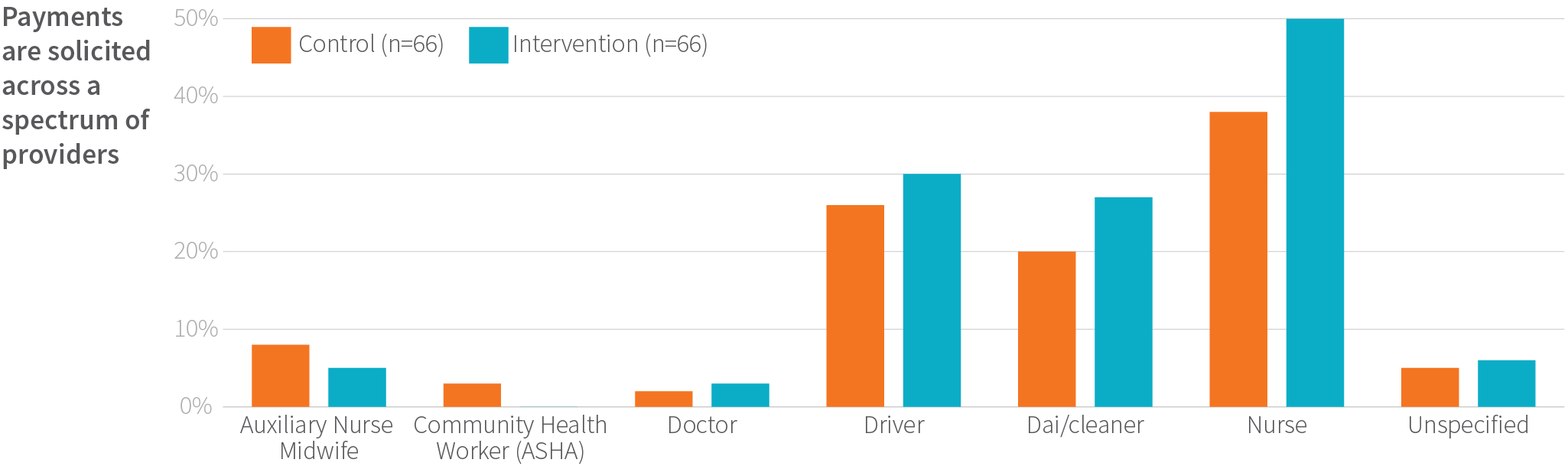

In fact, the BetterBirth Study found multiple people within the health system received payments. Among women reporting making informal payments, nurses were the most commonly remunerated, followed by ambulance drivers and facility cleaners. In the most extreme cases of financial pressure, nine out of 158 interviewed participants reported care was withheld until they paid.

The average payment for childbirth was equivalent to a family’s monthly income. If a complication occurred, women and families were often reluctant to be referred to a higher-level facility, because they were concerned about paying the customary expenses of additional care providers, ambulance drivers, and others. They were also leery about the unknown quality of care they would receive at the referral facility.

Women and Community: Key Recommendations

Improving the quality of care—both the provision and experience—requires focusing on women and their voices. Raising women’s expectations for care and preserving their dignity during childbirth are essential to high-quality, person-centered care. More broadly, women’s empowerment, including education, needs to be a priority. Women need to be heard and involved in designing initiatives that affect their health.

- Assess and improve financial systems that appropriately incentivize care through formal payments (i.e. timely and appropriate salary) and penalize informal payments across the continuum of care and levels of care.

- Develop metrics and methods for analyzing the drivers of disrespectful care and abuse, respectful care, and patient satisfaction and experience.

- Integrate respectful, person-centered care in birth attendant training. Such an approach should include strategies to communicate health-related information in ways women can understand and remember. Equipped with the appropriate knowledge (such as danger signs, advantages of exclusive breastfeeding, importance of immunizations, and family planning options), women are best positioned to care for themselves and their newborns once they return home after birth.

- Build programs to strengthen women’s agency in forming expectations and increase their power in demanding respectful, dignified maternal and newborn care. ■