To understand strengths and challenges in the quality of childbirth care, it is important to have reliable methods to measure progress. The BetterBirth Study implemented a variety of rigorous, customized approaches to ensure the collection of high-quality data in a setting of scarce resources, and uneven documentation of care at the facility level. We provide our measurement strategies and recommendations for researchers below.

Piloting and Adaptation

The BetterBirth intervention and implementation strategy resulted from an adaptive design process with implementation, evaluation, and feedback that demonstrated improved adherence to essential birth practices after iterative changes in multiple pilot sites.

Adaptation to create the BetterBirth intervention package used in the randomized controlled trial

| Karnataka Pilot | First adaptation | Second adaptation | RCT | |

| Leadership engagement | Study lead introduced to district and facility leadership | Nonstandardized introduction to district and facility leaders | Formalized introduction at district and facility including strong focus on motivation to drive adoption | Same as in second adaptation |

| Education of facility staff | One-day training on the Checklist supported by instructional video and hands-on simulation | 3-day training for staff (2 days didactic, one day coached practice using the Checklist) | Semi-structured launch including 1-2 day workshop introducing Checklist, problem solving and strong focus on motivation | Structured 2-day launch with increased focus on implementation of the Checklist with day 2 on-site for official start |

| Coaching support | Core team of head of facility, senior physician and labor nurse supplemented by physician from the study team. Coaching provided during normal clinical routines supplemented every 2 weeks by study physician Coach training through review of Checklist | Physician-led team of physicians and nurses coaching birth attendants Coaching provided every 1-2 weeks for 4-6 weeks Coach training through 2-day, on-site workshops focusing on clinical skills | Peer-to-peer model: nurse coaches for birth attendants (behavior change), physician coach for facility leader and childbirth quality coordinator (systems change and Checklist leadership) Coach training focused more on quality improvement approaches and behavior change | Same as in second adaptation with additional focus on district lead to build support for Checklist Coach training using standardized curriculum focused on coaching skills to drive behavior change and barriers framework (opportunity, ability, motivation) with strong focus on motivation |

| Data feedback loop | Subset of baseline observation data feedback to staff to identify quality gaps | None | Paper-based system used to capture and review observation data by team to identify persisting gaps and behavior change | Robust app-based system to provide real time data feedback on coach observations and essential birth supplies to Study team, facility and district |

| Safe Birth Supplies (SBS) | Largely available | Supply chain gaps identified | Increased focus of coach team leader to help head of facility, and district leaders leverage existing resources to address gaps | Strengthened focus for coaching and advocacy at facility and district levels to improve supply availability |

One important lesson learned in the pilot phase was the importance of peer-to-peer coaching (instead of physician-led coaching of birth attendants) and skills needed to effect behavior change in birth attendants.

The randomized controlled trial design ensured rigor but also limited the ability to adapt the intervention along the way. This constraint meant that refining the intervention and implementation approach during the piloting phases was crucial.

Baseline Mortality Measurement

We used existing facility register data from the year prior to the study to calculate baseline mortality rates in study facilities. Because of challenges with facility record-keeping and reporting prior to study initiation, it would have been preferable to do rigorous baseline measurement of mortality as part of the study.

We found that the BetterBirth intervention did not reduce perinatal mortality rates compared to change from baseline; perinatal mortality rates increased overall in both intervention and control arms, likely because of improved record-keeping and reporting.

Data collection for health outcomes

Facility-recorded outcomes

Across the 120 facilities, data collectors obtained birth event registration and follow-up data (demographic information relating to the woman and newborn; contact information for the family and the family’s community health worker/accredited social health activist; and data for in-facility survival outcomes for each woman-newborn dyad) from facility registers.

At the beginning of the trial, facility registers were at times incomplete and at some facilities did not exist at all. Leadership support and birth attendant buy-in was needed to address this gap. BetterBirth data collectors recorded information from registers twice per week during enrollment; this frequent oversight quickly improved the use and completeness of facility registers in both intervention and control sites.

BetterBirth data collectors recorded information on maternal or perinatal complications noted by the birth attendants in the facility registers. Unfortunately, named complications were not verified through a secondary means (physical exam, lab test, etc.), making interpretation more difficult. Additionally, we suspect that complications were significantly underreported. For example, among the 44,515 infants with documented weight less than 2,500 grams, only 11% were noted to be low birth weight.

Primary Outcomes

Primary outcome for the trial was the rate of a composite measure of maternal, fetal, and newborn outcomes that occurred from birth to 7 days after birth. Specific outcomes comprising the composite measure included:

Maternal outcomes:

- Maternal death within 7 days: death of a woman at any time from admission to the facility for childbirth, through delivery, until 7 days following delivery;

- Severe maternal complications within 7 days: Defined by the following clinical criteria: fits (in absence of history of epilepsy,) loss of consciousness retained at >1 hour, high fever and foul smelling vaginal discharge, postpartum hemorrhage, or stroke.

Fetal and Neonatal outcomes:

- Stillbirth: fetal death occurring at ≥28 weeks of gestation OR with a birth weight of ≥1000 gm at birth, including both fresh and macerated stillbirths;

- Early neonatal mortality: newborn death that occurred in the first week of life.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes for the trial included:

Combined maternal, fetal and newborn outcomes:

- composite rate of maternal death within 7 days,

- fresh or macerated stillbirth, and

- neonatal death at 7 days.

Maternal outcomes:

- Rate of maternal death (measured through 7 days after delivery),

- rate of severe maternal complication described above (measured through 7 days after delivery),

- rate of inter-facility transfer, and

- the rates of the following maternal procedures: blood transfusion, hysterectomy, need to revisit facility due to a problem, C-section.

Newborn outcomes:

- Fresh or macerated stillbirth,

- rate of early neonatal death (within 7 days),

- rate of inter-facility transfer,

- need to revisit facility due to a problem.

Rates of adherence by health workers to essential childbirth practices (“process measures”):

- maternal temperature obtained on admission,

- maternal blood pressure obtained on admission,

- partograph use,

- inappropriate initiation of oxytocin before delivery of the baby,

- appropriate hand hygiene (use of soap and water, and wearing clean gloves) by health workers at the time of delivery,

- skin-to-skin care, oxytocin administration within 1 minute after birth,

- newborn weight and temperature obtained within 1 hour after birth, and

- initiation of breastfeeding within 1 hour after birth.

Patient self-reported outcomes

- Total sample: 157,689 births across intervention and comparison facilities.

- Inclusion criteria: all women admitted to a study site for childbirth. Exclusion criteria: women referred into the study facility from a subcenter, those being managed for abortion, and those who did not provide consent.

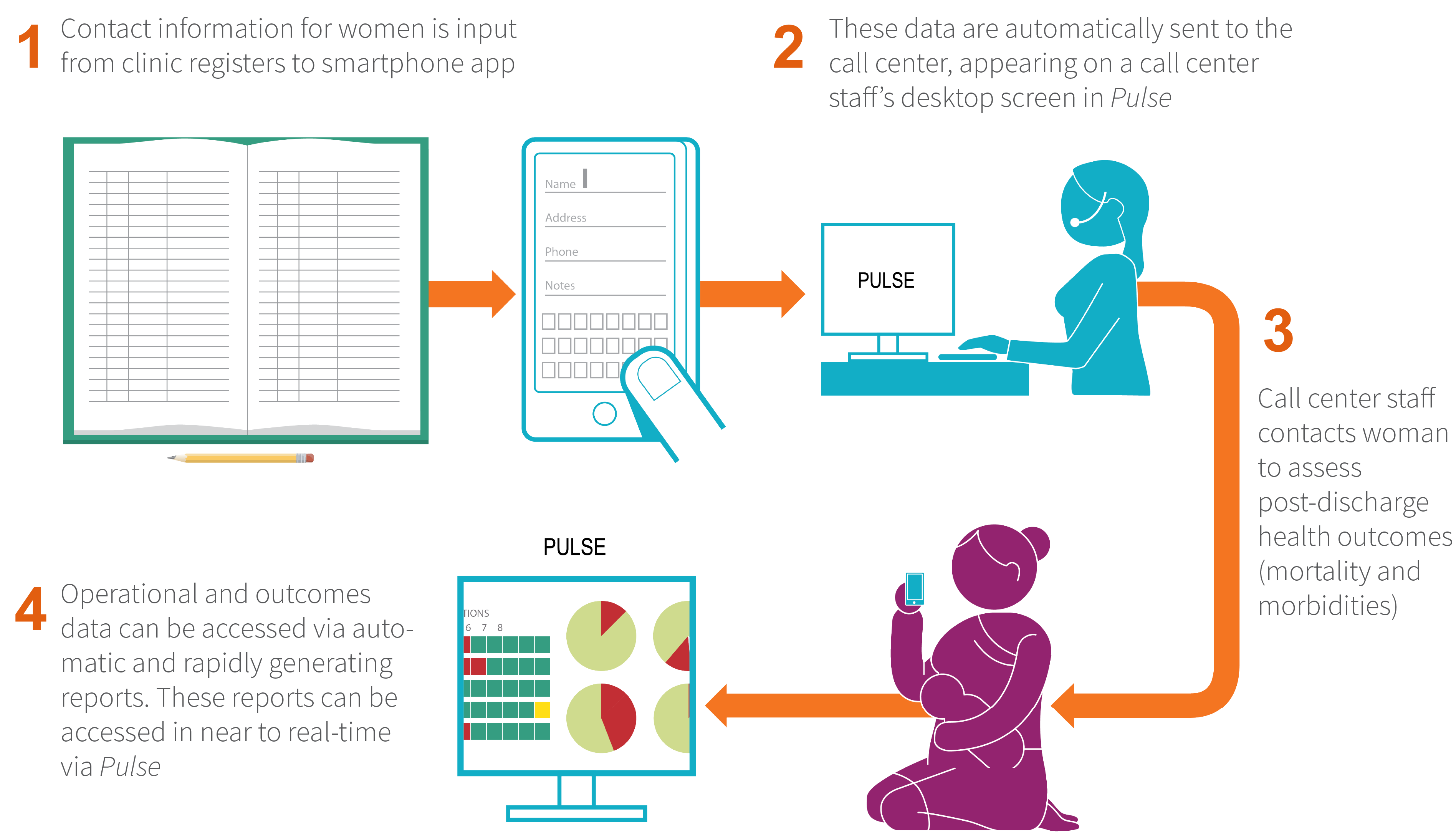

- Female call center personnel followed up with woman-newborn dyads via phone call (or through a home visit when needed) between eight to 21 days post-childbirth to ascertain patient-reported outcomes, including maternal severe morbidity, maternal mortality, and perinatal mortality.

- Loss to follow up: 0.3% of women eligible for follow-up.

- The call center was also used to collect additional information on patient satisfaction, family planning practices, and women’s understanding of postpartum danger signs.

- At the end of follow-up calls or visits with women and/or their families to collect health outcomes, two additional questions were used to assess patient satisfaction:

- “How satisfied are you with the care you received at this facility?” (Very satisfied, Somewhat satisfied, Somewhat unsatisfied, Very unsatisfied)

- “How likely are you to recommend this facility to your friends or family for their delivery?” (Very likely, Somewhat likely, Somewhat unlikely, Not likely at all) The BetterBirth call center was effective, with high accuracy and validity, in ascertaining health outcomes. In an under-resourced and geographically vast setting with high cell phone coverage, the call center successfully followed up with the large majority of women.

- These questions were only asked to women or their husbands, not to more distal family members. Satisfaction-related questions were not asked in any cases where a maternal or perinatal death occurred.

- At the end of follow-up calls or visits with women and/or their families to collect health outcomes, two additional questions were used to assess patient satisfaction:

- The call center was very acceptable to women and less costly than home visits for follow-up.

Direct Observation of Care

Independent observers

Trained data collectors (all nurses) directly observed health workers that attended to women and their newborns around the time of birth, and at the first three of the four Checklist pause points in a subset of 30 facilities (15 intervention, 15 comparison matched pairs). Observations were conducted at baseline (10 facilities), after two months of coaching (30 facilities), after six months of coaching (10 facilities) and four months after the end of coaching (30 facilities). Direct observation was intended to measure the impact of the Safe Childbirth Checklist intervention on delivery of essential birth practices, as a secondary outcome. A convenience sample of women and newborns cared for by the health workers around the time of childbirth during data collectors’ daytime duty hours was included in this component of the study. The aim was to obtain approximately 60 observations at each observation point (on admission, before pushing, within one minute of delivery, within one hour of delivery) per facility per data collection period. Checklist pause point four was not observed because of the uncertain time and place of discharge in these facilities. Facility-based data associates observed and recorded activities in the admission, labor and delivery, and postpartum wards. Data was recorded on standardized (paper-based) data collection forms and then entered onto a mobile application.

Coach observers

In the 60 intervention sites, coaches also collected data on Checklist practices conducted by birth attendants at each coaching visit over the eight-month intervention. While the coaches’ main role was not data collection, but rather to help facility staff document gaps in care and work towards improvement, the study capitalized on their presence at facilities to obtain additional observation data. Behaviors as observed by coaches were documented across all four pause points of the Checklist.

Other Data Sources

Additional quantitative and qualitative data were collected via multiple methodologies (see Appendix B for further details), including

- Quarterly surveys of supply availability at all facilities and biweekly surveys of supply availability at intervention facilities during the eight months of coaching;

- Self-administered surveys of birth attendants in intervention facilities to assess 1) Checklist use and acceptability, 2) safety culture, and 3) time use;

- Systematic collection of birth attendant characteristics;

- Tracking of facility-level leadership changes (medical officer in charge, medical superintendent, childbirth quality champion);

- Time-motion and work-sampling observations of health care workers to assess time spent on Checklist-related activities and overall distribution of time at facilities.

- Total administrative costs of the intervention;

- Verbal autopsy interviews with families who had experienced a stillbirth or early neonatal death during the study;

- Interviews with birth attendants across three categories of facilities: facilities with high uptake of the intervention, facilities with moderate uptake of the intervention, facilities with minimal uptake of the intervention;

- Focus group discussions with coaches and BetterBirth research staff; and

- Verbal surveys of women on satisfaction with care, knowledge of danger signs, and family planning practices.

Data Quality Assurance

The study included a robust, multi-component data quality monitoring and improvement system (DQMIS) that ensured high-quality data for health outcomes and directly observed care throughout the BetterBirth Study. Functional components of the system included

- in-country monitoring and evaluation team to support data management and quality;

- standard operating procedures and tools for data collection;

- research staff training for data quality;

- an electronic data collection and reporting system that allowed for real-time data feedback for use in coaching; and

- DQMIS protocol including data collection audits, rapid data feedback, and supportive supervision.

DQMIS activities were carried out by data collectors and their supervisors across all data collection workflows, and focused on ensuring consistency and accuracy in data collectors’ recording of information; proper transfer of data from paper-based to electronic formats; and ongoing supportive supervision of field workers regarding data collection.

To ensure high-quality implementation of the intervention package, implementation teams conducted progress reporting, and designated supervisors conducted in-person monitoring visits to observe the quality of implementation, validate data on implementation progress, and compare achievements against predefined benchmarks.

Message Synthesis Process

With the abundance of data produced by the BetterBirth Study, we underwent an iterative process to analyze and interpret primary and secondary outcomes and to integrate those findings with additional insights collected through qualitative interviews, surveys, and process measures. The goal of the process was to produce messages that are relevant, innovative, and actionable for implementers and policymakers, both globally and in Uttar Pradesh. During this eight-month process, messages were developed and distilled through a series of meetings with other global implementation experts, policy experts, researchers, representatives from professional organizations, and government officials.

Recommendations

- Conduct rigorous baseline data collection to better understand impact of the intervention in complex health systems.

- Consider adaptive trials or other implementation science strategies for complex interventions. Multiple adaptations of an intervention may be necessary to maximize the impact of a quality improvement initiative.

- Use mixed methods to measure process indicators on how/why implementation is working or not working, where the barriers/gaps are, and how they are addressed, in order to contextualize the outcome measures.

- Incorporate added measurement of behaviors for the cascade of actions following Checklist items (i.e., if measured blood pressure was high, was the patient given magnesium sulfate? If maternal temperature was high, was she given antibiotics?).

- Cost-effectiveness, which is often left out of program evaluations, should be included.

- Invest in mechanisms or systems to minimize loss to follow up and maximize accuracy of data, such as

- Mobile/electronic data-capture systems;

- Call centers for outcome measurement; and

- Systems for data-quality assurance.