As part of the global shift to facility-based childbirth with skilled birth attendants, the BetterBirth intervention centers on the implementation of the World Health Organization Safe Childbirth Checklist to improve quality of care in facilities.

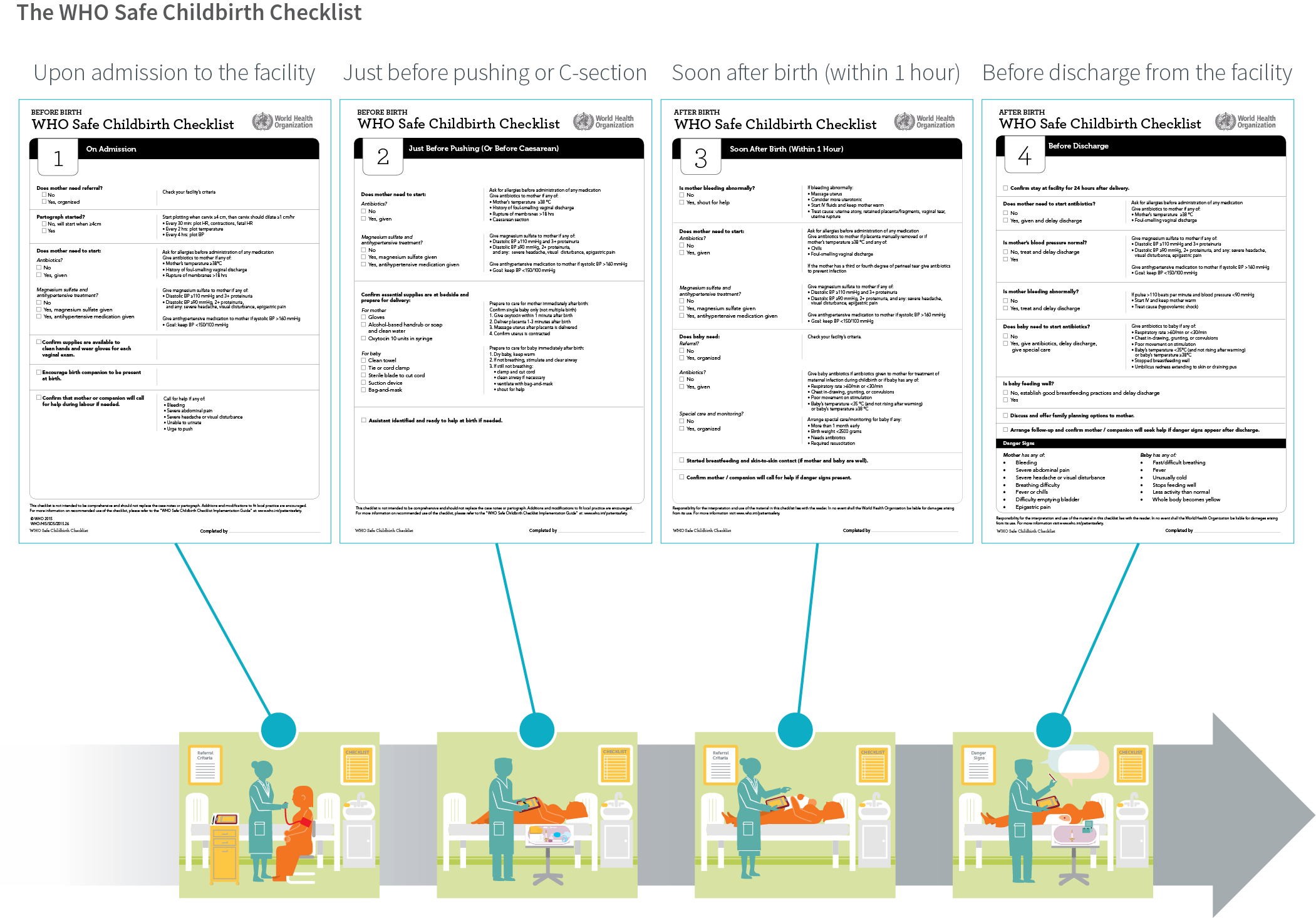

The Checklist was created in 2009 to ensure key evidence-based practices during labor and delivery were provided to every woman and newborn, every time. The WHO Checklist was developed through a rigorous process in which experts identified 28 essential birth practices that prevent the major causes of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.

The Checklist divides these practices into four “pause points,” or moments to remind birth attendants to follow the practices: on admission, just prior to delivery, within one hour of birth, and before discharge.

The Checklist was designed as a clinical reminder and as an accountability tool to identify gaps in care delivery and essential supplies. Its primary purpose is to hold birth attendants accountable for adhering to key practices, but it also holds leaders accountable for restocking supplies and addressing other barriers.

THE CHECKLIST IN ITALY

A teaching hospital in Florence, Italy, implemented the WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist as a tool to support health-care workers managing critical activities during delivery. Results demonstrated improved interdisciplinary teamwork and communication.8

The BetterBirth Study was a randomized controlled trial of an intervention package that supported the WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist implementation. Control sites participating in the study received standard care. For the intervention sites, the BetterBirth partners recognized that a checklist alone would not reduce childbirth-related deaths or complications. Therefore, the intervention was paired with an implementation strategy of engage-launch-support.

As part of the study’s engagement campaign, leaders at the facility, district, and state levels were solicited for their views on and commitment to the Checklist, which had been adapted to India’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare guidelines.

An inspirational launch event formally introduced the Checklist to each facility, motivated birth attendants, and assessed existing gaps that could hinder its adoption.

The support strategy used peer-to-peer coaching to build trust between birth attendants and coaches. These coaches—trained nurses employed by an independent, external organization—worked directly with birth attendants. The coaching had three primary goals:

- to motivate birth attendants to change their practices,

- to observe, record, and share information about birth attendants’ behaviors to facility and district leaders in order to increase system-level support for improved quality of care, and

- to support birth attendants in their efforts to problem-solve and overcome barriers to essential practices.

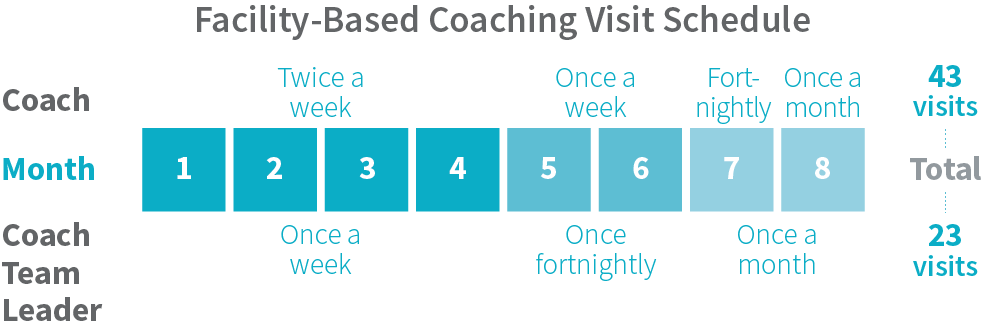

Coaches visited each facility twice weekly during the early stages of the intervention, with the frequency of visits decreasing to once monthly by the end of the intervention, for a total of 43 visits over an eight-month period. Due to the study design and requirements, the support strategy could not be adapted from facility to facility.

Coaches did not provide clinical care, specific training in birth attendant competency, or medical supplies; rather, they supported the birth attendants and leaders to activate resources within their own facility. Although coaches did not intervene in emergencies, they did have the authority to communicate any concerns to the medical officer in charge, if needed. Coaches also had the discretion to encourage appropriate referral of a woman or newborn before, during, or after observation, since such measures are explicitly spelled out in the Safe Childbirth Checklist.

Coach team leaders focused on supporting the facility leadership and ensuring strong communication between frontline birth attendants, facility leaders, and district-level leaders. By enhancing communication, team leaders were able to more quickly identify deficiencies in supplies, staffing, and skills, while encouraging facility leadership to problem-solve these gaps.

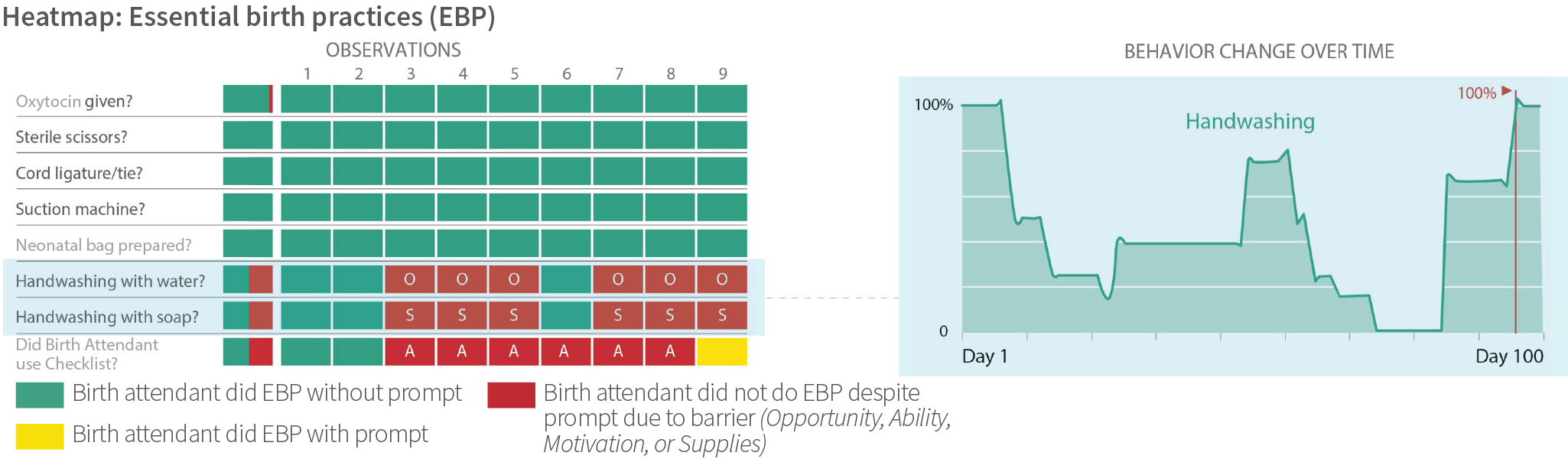

Data-feedback strategies at the facility and district levels included sharing heat maps, a data visualization tool, of adherence to essential birth practices. This feedback process was carried out in a collaborative and nonpunitive manner through sharing data results in aggregate rather than at the individual level. The purpose was to hold birth attendants, coaches, and leaders accountable for improving adherence by addressing opportunity, ability, and motivation barriers. District health personnel benchmarked facility-level behavior change to track improvement over time.

At each facility, a motivated and respected staff member was selected by facility leadership to be a childbirth quality champion. The champion worked closely with team leaders to improve quality of care and support the Safe Childbirth Checklist beyond the BetterBirth Study.

Key Findings from the BetterBirth Study

Implementation of the WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist in primary facilities improved overall uptake of and adherence to essential birth practices. Among the study’s findings:

- After two months of coaching, birth attendants who received coaching and the Checklist had higher adherence to practices than birth attendants in control facilities (2,563 births observed). After the intervention was completed, birth attendants who received the intervention maintained higher adherence to practices compared to birth attendants in control sites (2,325 additional births observed).

- In the presence of a coach, birth attendants were often able to overcome pressures such as misaligned clinical and financial incentives.

- Adherence was lower when the coach was not present and the birth attendant was observed instead by an independent data collector.

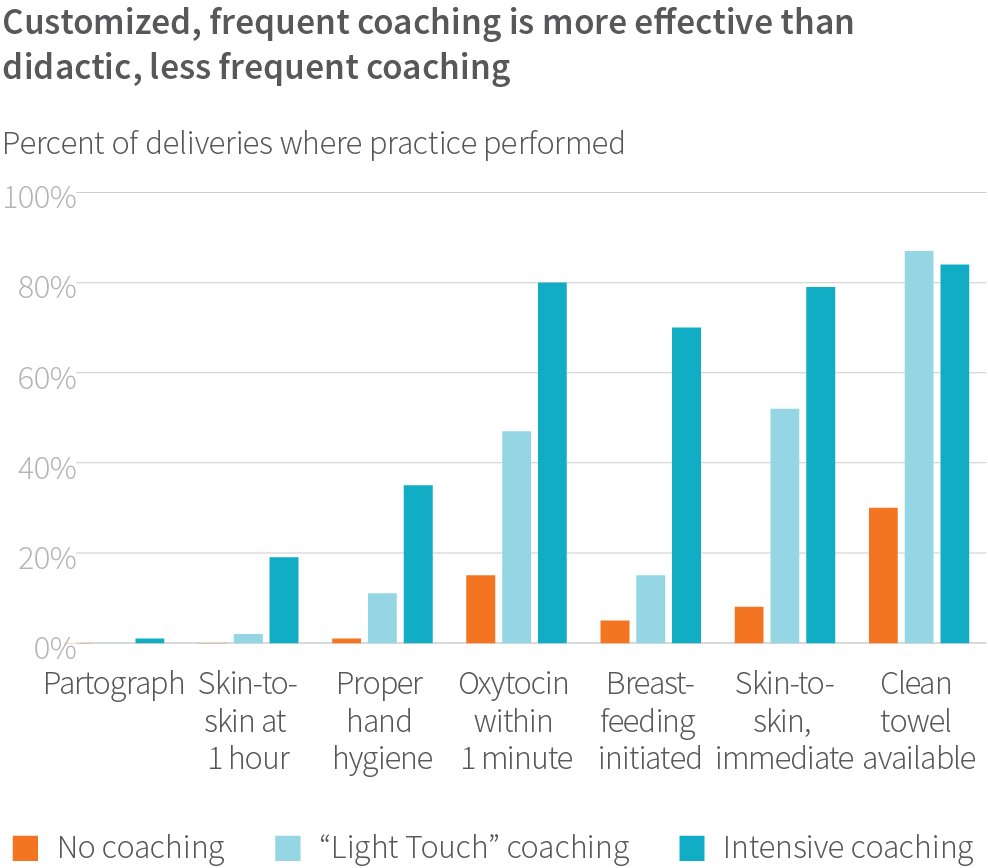

- After study completion, a shorter, “light touch” intervention was implemented in control facilities. In this intervention, coaching occurred through 10 visits over eight weeks and used a prescriptive training program. We found that adherence to essential birth practices was lower in the “light touch” group compared to the birth attendants who received the full intervention (1,210 births observed during “light touch”).

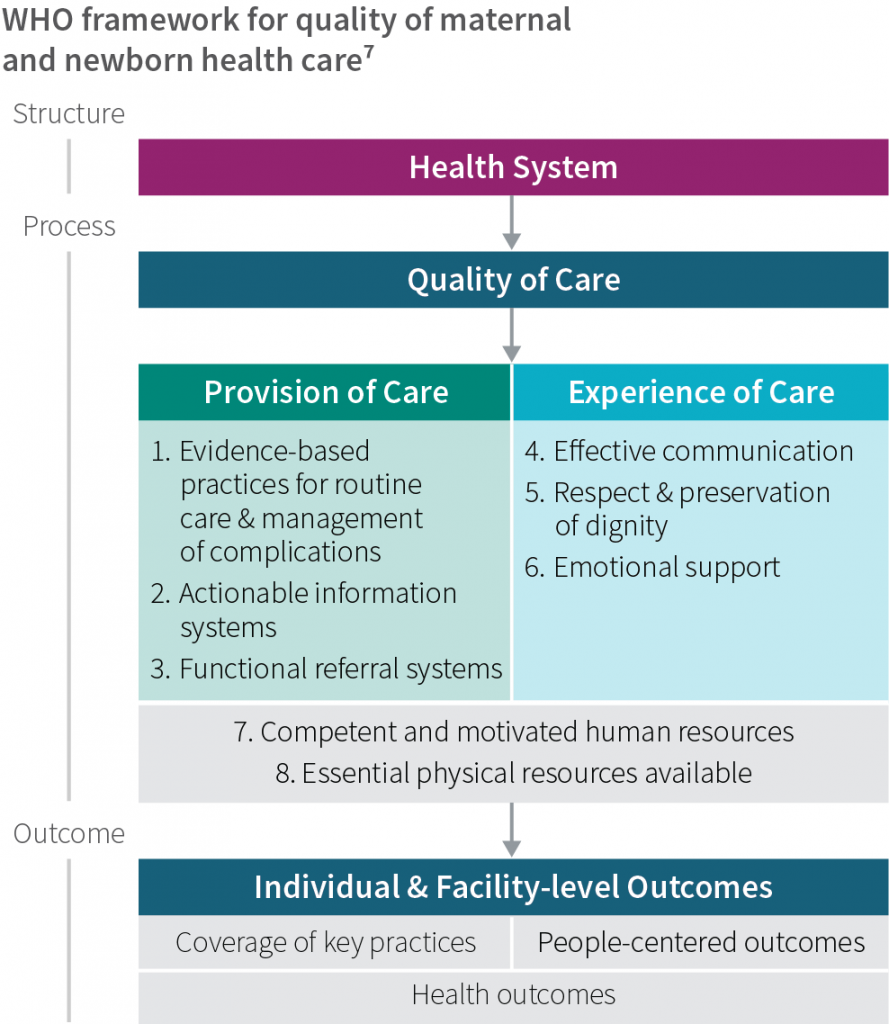

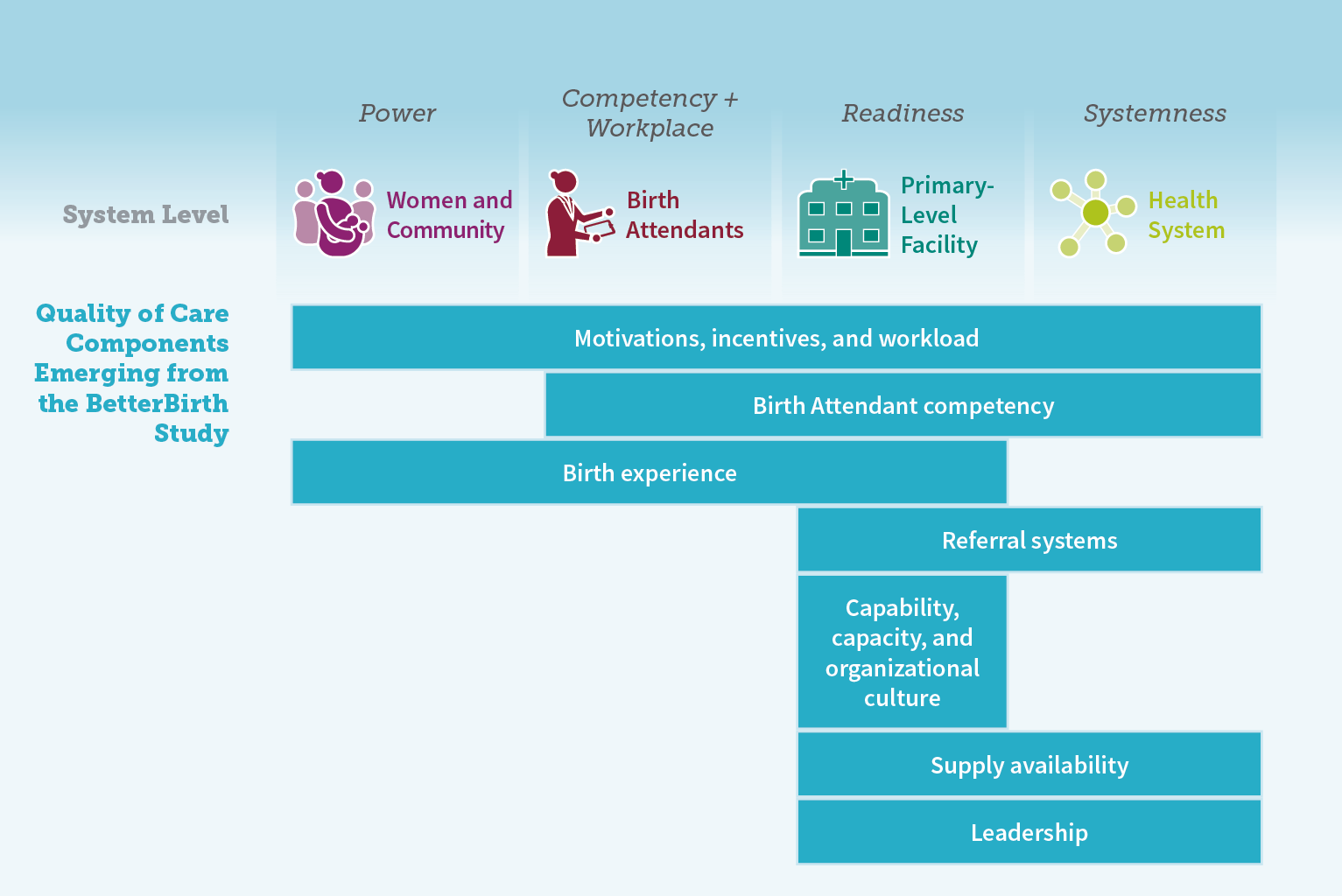

The BetterBirth Study showed behavior change is possible. It also demonstrated that more is required to enhance quality and actually improve maternal and newborn health outcomes. The WHO Quality of Care Framework,7 published in 2016, defines the two most important domains of quality as 1) the provision of care and 2) the experience of care among women, newborns, and their families. In the BetterBirth intervention, the provision of care was defined narrowly as adherence to 28 essential practices. While this specific goal was a prerequisite for improvement, it did not suffice to reduce morbidity and mortality.

This unexpected result may stem from the fact that the BetterBirth intervention was not designed to improve other quality-of-care components, including

- birth attendant competency;

- motivations, incentives, and workload;

- emotional support, respect, and dignity for women and their families; and

- referral systems.

Such insights from the study highlight the need to widen the focus beyond one single component of health-care quality, and instead to acknowledge and leverage the interdependence and connectedness of all components.

Additional Insights from around the Globe

After initial pilot testing of the Safe Childbirth Checklist, the WHO created a global collaborative in 2012 to understand how the Checklist could be adapted to different contexts. The WHO and Ariadne Labs drafted an implementation guide to accompany the Checklist, following a survey that had been administered among its collaboration sites to assess the factors that promoted or hindered Checklist use. Findings from both global sites and the BetterBirth Study were incorporated into the guide. More than 30 sites participated in this collaborative to share how they adapted strategies and coaching models to fit their unique needs, constraints, and local customs.

Many sites that employed a coaching model used coaches who were based within their facilities and had strong, established relationships with peers and leaders. These coaches identified knowledge and skills gaps, and addressed the gaps through a variety of strategies, including clinical trainings, simulations, and real-time skills-building workshops. Coaches were either leaders within the facility or were otherwise institutionally connected to facility leaders—positions that gave them the authority to take action when needed to overcome hurdles to Checklist use, such as stock outs or staffing problems. These interpersonal and organizational relationships within the health facilities ensured that participants were accountable to each other, which in turn eased adoption of the essential birth practices and encouraged other positive behavior changes over time.

Now that the WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist has been disseminated globally, new insights have emerged from implementers. The main learnings from the Collaborative are captured in a new report, WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist: Lessons from the Field, and offer further strategies for implementation success. An overarching theme is that the Checklist must be locally owned, adapted, and implemented to ensure its relevance, acceptability, and successful uptake. At the same time, stakeholder engagement across the health care system—from frontline users to facility managers to state leaders—boosts Checklist adherence. The WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist was most often successful as part of a larger quality improvement initiative, including skills labs, maternal death audits, and quality improvement cycles.

The WHO global collaborative enabled implementers to share successes and challenges, and to discuss further strategies to improve quality of care in childbirth. Topics discussed included how to counter staff resistance to using the Checklist; how to enhance understanding of Checklist tasks; and how to improve clinical skills. Additionally, implementers from around the world shared how they used the Safe Childbirth Checklist to encourage accountability in clinical decisions and to improve supply chains.

ADAPTING THE CHECKLIST IN SRI LANKA

The WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist was implemented in the University Obstetrics Unit at De Soysa Hospital for Women, Colombo, and two obstetric units at Teaching Hospital, Mahamodara, Galle, Sri Lanka.

The implementation team adapted the original Checklist to fit into their local context by adding the use of antenatal corticosteroids to the Checklist and encouraging the presence of a labor companion. They also modified the first two pause points—the first point was advanced to admission to the antenatal ward; the second point became admission to the labor ward.9

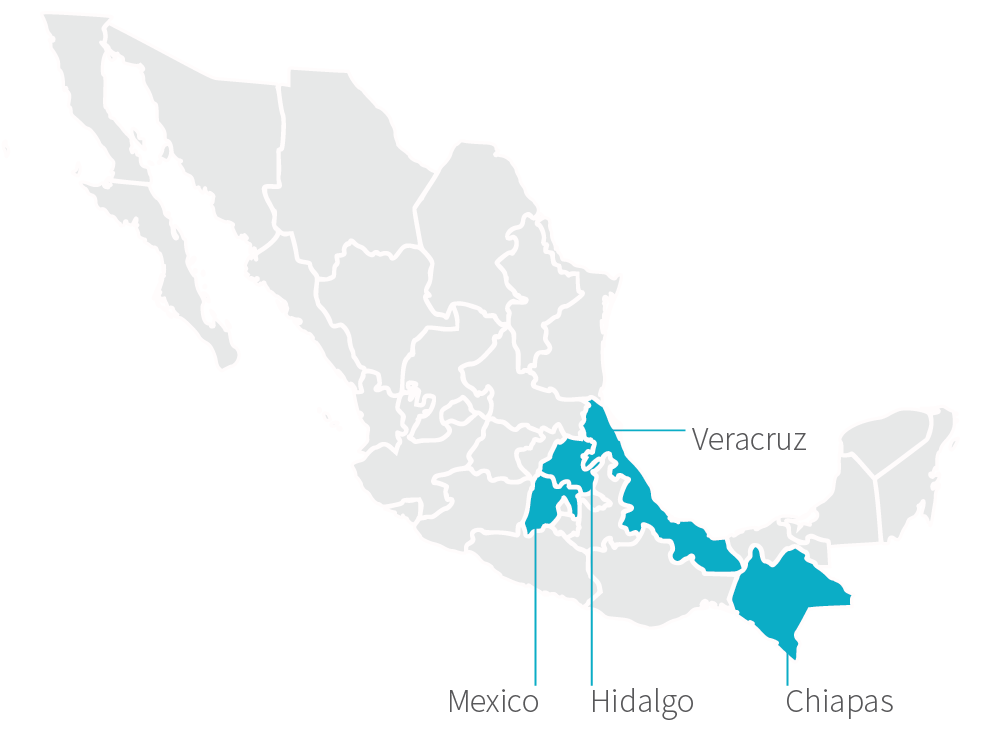

ADAPTING THE CHECKLIST IN MEXICO

A working group was established with the participation of the obstetrical, perinatology, and quality management staff from four hospitals in the state of Hidalgo, the state of Mexico, and Mexico City, supported by a research team from the National Institute of Public Health.

This group spent time adapting the Safe Childbirth Checklist to the local context prior to implementing it. For example, the original WHO Checklist is a single document including practices for women during labor and delivery, and for newborns after birth. This group separated the Checklists (one for women and another for newborns) to better incorporate additional childbirth care responsibilities into the Checklist.

Additionally, the original Checklist asks if there was a cesarean section. In Mexico, they added a check on the reason for the cesarean section, according to a list proposed by the working group based on accepted practice guidelines.10

Key Recommendations

In future implementation of the BetterBirth intervention and similar quality improvement initiatives, the tool and implementation strategy should be adapted to the local context. Below are recommendations to facilitate adaptation of each component of the BetterBirth intervention.

Safe Childbirth Checklist

- Clarify the purpose of the Checklist (i.e., decision support, memory aid, accountability tool) and the intended users (i.e., individual birth attendants, teams of birth attendants).

- Ensure that the Checklist is supported internally and that it meets an identified gap at the facility.

- Support real-time use, not just retrospective documentation, through identifying and supporting champions.

- Consider adapting and/or editing the Checklist and its pause points, or introduce the Checklist through a step-wise process, according to the facility’s workflow constraints.

- Ensure an adequate supply of paper Checklists or use electronic Checklists.

- Consider linking the Safe Childbirth Checklist with other safety bundles, crisis checklists, or cesarean checklists, to better manage complications.

Coaching

- Coaches should be appropriately trained and empowered to develop strong relationships, provide effective and nonjudgmental feedback, and define a clear process for problem solving.

- Ongoing supportive supervision for coaches themselves is needed to continually build skills and share problem-solving strategies.

- Consider intensive and/or ongoing coaching to achieve and sustain adherence to essential birth practices.

- Coaches should be able to support and empower birth attendants to identify and address barriers to behavior change in real time.

- Provide coaching to all birth attendants and across all pause points, including during night shifts.

- Ensure that coaching for quality improvement initiatives includes mechanisms for accountability and reaches facility-, district-, and state-level managers in addition to birth attendants.

- Facility leaders should strive to create a synergistic relationship with coaches to uphold the quality improvement intervention.

- Coaches should recognize and address existing incentives (e.g., financial and social expectations of childbirth care) that influence birth attendant behavior as part of their coaching approach.

- Coaches should be flexible in adapting their strategy based on birth attendant needs, rather

- than strictly following a rigid coaching curriculum or protocol.

- Coaches may benefit from a government title or other form of institutional empowerment, rather than operating as external project personnel separate from the local health facility.

- While implementation partners around the globe reported success with coaches who came from within facilities, further research is needed to evaluate the impact of internal versus external coaches.

Data Feedback

- Incorporate human-centered design in developing data feedback platforms, including user-friendly data visualization and integration with systems that routinely collect information.

- Ensure that data-feedback mechanisms are not used to punish staff, but rather to constructively address gaps in care and hold systems accountable for improvement. ■